Volume 8, Issue 8 - September 2025

|

Professionalism and Ethics in Dentistry

By: Bryan Pilkington, PhD

|

I teach an elective course for medical students on ethics and the Hippocratic Oath. It is one of the most enjoyable courses to teach because it opens up space for students to explore the ethical nature of their chosen profession and because I learn a great from our conversations. In a recent class session, I was impressed by the role that trust plays in their thinking about health professions, health systems, and importance of the Hippocratic Oath (or one of its descendants) for building and maintaining trust in healthcare. As a patient and as person who is responsible for the care of some smaller patients, trust I crucial. Health professionals ought to strive to be clear, transparent, and honest: doing so can engender trust with patients; failing to do so can damage relationships that are essential for good healthcare. I learned this the hard way after a few visits to a pediatric dentist. Being new to an area, and relying on recommendations from a pediatrician, I was happily surprised by the ballons and other nice distractions that were offered but most appreciative of those five key words any parent (or perhaps any patient) waits to hear, “Yes, we take your insurance.” Having paid upfront for services that would then be reimbursed for – per the dental practice’s policies – I was a bit confused why the promised reimbursement checks never came. As life gets busy, things get missed. I inquired a few times, usually at the next visit, and was told the office would check into things. At what turned out to be the final visit (one in which the patient was not even seen by “their dentist,” I learned from a chattier receptionist I had not yet met that the dentist was not quite living up to their end of the reimbursement bargain. The story about submitting claims to insurance was true, but they did not, in fact, participate with my insurance. They would – l learned later that this is not the only dental practice who uses terms this carefully – “take” my insurance and submit it, but there was no expectation of an insurance company paying and thus not expectation of the dentist reimbursing me. I teach an elective course for medical students on ethics and the Hippocratic Oath. It is one of the most enjoyable courses to teach because it opens up space for students to explore the ethical nature of their chosen profession and because I learn a great from our conversations. In a recent class session, I was impressed by the role that trust plays in their thinking about health professions, health systems, and importance of the Hippocratic Oath (or one of its descendants) for building and maintaining trust in healthcare. As a patient and as person who is responsible for the care of some smaller patients, trust I crucial. Health professionals ought to strive to be clear, transparent, and honest: doing so can engender trust with patients; failing to do so can damage relationships that are essential for good healthcare. I learned this the hard way after a few visits to a pediatric dentist. Being new to an area, and relying on recommendations from a pediatrician, I was happily surprised by the ballons and other nice distractions that were offered but most appreciative of those five key words any parent (or perhaps any patient) waits to hear, “Yes, we take your insurance.” Having paid upfront for services that would then be reimbursed for – per the dental practice’s policies – I was a bit confused why the promised reimbursement checks never came. As life gets busy, things get missed. I inquired a few times, usually at the next visit, and was told the office would check into things. At what turned out to be the final visit (one in which the patient was not even seen by “their dentist,” I learned from a chattier receptionist I had not yet met that the dentist was not quite living up to their end of the reimbursement bargain. The story about submitting claims to insurance was true, but they did not, in fact, participate with my insurance. They would – l learned later that this is not the only dental practice who uses terms this carefully – “take” my insurance and submit it, but there was no expectation of an insurance company paying and thus not expectation of the dentist reimbursing me.

This experience has heightened my interest in dental ethics and health care professionalism in dentistry. This particular issue of The Academy is a long time coming and I want to share both my excitement for the conversations that it will engender and my gratitude to the excellent contributors. In our first article, “Reimagining Professionalism in Oral Healthcare - A Call for Defining Oral Health Justice,” Carlos Smith brings together global health concerns and professionalism considerations, ultimately arguing for the defining and pursuit of oral health justice. The case made is compelling and the theme of trust plays an important role, as Smith conceptualizes a holistic framework which, if realized, might “cultivate a greater trust in healthcare systems.” The second article in this issue is authored by the noted bioethicist and dental ethics scholar, Nanette Elster. Elster argues in favor of community water fluoridation and for the role that the dental profession must play in upholding this important public health measure. She writes, “Based on flawed rationales and outright misinformation, public mistrust and distrust is being fueled;” helpfully adding to the ongoing conversation about trust, health, and professionalism.

The third article is the next installment of Fred Hafferty’s Swick Test series. For those who have taken an interest in this ongoing series or who have questions about the Swick Test or dental ethics and dental professionalism, do write us. The issue concludes with the usual announcements from members, reminders about roundtables, and other healthcare professionalism-related news.

Bryan Pilkington, PhD, is Professor of Bioethics, in the Department of Medical Sciences, at Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, and the Editor-in -Chief of The Academy.

|

The Academy for Professionalism in Health Care - Call for Proposals: Deadline September 8

|

Professionalism in a Time of Change

Wednesday, November 12 and Thursday, November 13, 2025

8:00 am ET - 1:00 pm ET daily

via Zoom

APHC is an inclusive international organization which welcomes all professionals and their trainees who are devoted to the study and advancement of professionalism in health-related fields. The virtual conference will take place using Zoom. In addition to the presentations and sessions generated by this Call for Proposals, the conference will also include Keynote Presentations, Symposia, a Fireside Chat and ample opportunities to network with colleagues.

The submission deadline is Monday, September 8, 2025 at 11:59 p.m. EST.

Here is the link for more information and for the submission: 2025 November Abstract Submission

Back to Table of Contents

|

Reimagining Professionalism in Oral Healthcare - A Call for Defining Oral Health Justice

By: Carlos S. Smith, DDS, MDiv, FACD

|

Across multiple disciplines, arenas, and specialties; health disparities and inequities remain, and in some cases are worsening. The area of oral health is no exception and perhaps sits atop a proverbial mountain of healthcare problems. In fact, untreated dental decay, also known as dental caries or tooth decay, is the most common health condition globally, affecting billions of people. The World Health Organization adamantly states, “oral diseases, while largely preventable, pose a major health burden for many countries and affect people throughout their lifetime, causing pain, discomfort, disfigurement and even death.”1 With such a global [and domestic] burden of disease, do oral and overall health professions identity, values, professionalism and ethics inform this seemingly insurmountable burden?

In a broad sense, the systems of oral healthcare delivery often narrowly focus on ethical conduct in a one-on-one patient encounter, subsequently absolving both individual clinician and the profession as a whole from a holistic and systemic interrogation of professional duty and responsibility. Classic notions of professionalism—centered on clinical competence, principle based behavior, regulatory standards, and even appearance—seem insufficient in addressing the systemic inequities that plague oral health. What’s needed is a bold reimagining of professionalism that places oral health justice at its core: a commitment to advocacy and health equity that transcends the lone dental operatory and reaches into communities, policies, and institutions. While the classic pillars of professionalism remain essential, they often fail to confront the broader social, political and commercial determinants of health that shape oral outcomes. For example, access to care remains deeply unequal, with rural, low-income, marginalized, and minoritized populations facing significant barriers. While cultural competence and cultural humility frameworks once held promise, the concepts are inconsistently taught and practiced. Furthermore, the current political realities of dismantling diversity, equity and inclusion across the educational landscape and even accreditation standards will likely lead to even greater miscommunication and mistrust. Health workforce diversity already lags behind, limiting representation and culturally responsive care. Thus professionalism must evolve from a static code of conduct to a dynamic ethos of justice—one that recognizes oral health as a human right and demands systemic change.

A call for further examining professionalism and dental ethics, both theoretically and by application, is not new.2 In medicine, “a professionalism of solidarity enacted through critically conscious reflection addressing the reality of a world in which healthcare systems are key components of structural inequities” has been proposed.3 Across the health professions, wellbeing and wellness are being understood as key components of professionalism.4-6 Even in dentistry, a redefining of what it means to be professional “will include better defining the relationship with patients and society so we can begin discussions with others as partners sharing a common future. That means dentistry will not be the only voice for determining what is ethical. Others are also moral agents whose choices about what is right and good have the same kinds of effects on the profession that dentists’ choices have on them.”7 Perhaps the social contract is a necessary launch point, however scholars have called into question the supposed benignness of social contract theory in and of itself.

“The absence of anti-oppression notions in the traditional social contract and even professionalism at large cannot be understated…Particularly, in the United States, the profession is able to opt out of its social contract to provide oral healthcare as a means of health justice by offering care through community service. Whether this is via coordinated service events or targeted outreach to ‘underserved’ communities, this work is not about improving access to care and fulfilling an obligation to society. To be clear, justice as merely fairness is largely relegated to community service. Community service conveniently allows for an equity-deprived, non-disruptive, almost self-aggrandizing form of professionalized patting of oneself on the back for a job well done in maintaining the status quo of disparity, with no real clarion call for addressing the systemic ills rendering community service of need in the first place.”8

Likewise, the inclusion of social activism as a core generational value for current students, residents and young professionals, aligns with a reframing of or advancement of a new professionalism definition. Social advocacy must be seen and understood as part and parcel of ethical responsibility. Dentists must see themselves not only as clinicians but as advocates. This could include: a) speaking out against policies that perpetuate inequity, b) supporting legislation that expands access to care rather than doubling down on the profession’s own entrepreneurial identity and capitalistic sensibilities, and c) partnering with community organizations to address local needs. Key to that reframing is an expansion of previous definitions to allow for intervention mechanisms, systems and practices – not simply refraining from doing harm but actively interfering or taking action if wrong is being witnessed.9 A justice oriented approach could even become the lens through which one views other classic ethical principles. Take beneficence for example, while nonmaleficence grounds one in a duty and responsibility to refrain from harm, beneficence most commonly is understood as doing good. But what if that refraining harm coupled with doing good had a justice lens, to not simply avoid doing harm, but includes intentionality to benefit patients, promote their welfare, and remove conditions that cause harm.10

Oral health justice is more than equitable access to dental services. It could be a holistic framework that a) centers marginalized voices in the design and delivery of care; b) addresses structural racism, economic inequality, and geographic disparities; c) promotes community engagement and empowers individuals to advocate for their own oral health; and d) Integrates oral health into broader public health and social justice movements such as reproductive justice. Redefining professionalism through the lens of oral health justice has ripple effects beyond dentistry. It contributes to improved overall health outcomes, as oral health is deeply connected to systemic health. It could also cultivate a greater trust in healthcare systems, especially among historically excluded groups. This reimagining of professionalism and centering justice could offer a more resilient and responsive workforce, equipped to meet the challenges of a changing society. Moreover, it aligns oral healthcare with global movements for health equity, human rights, and social justice—positioning the profession as a leader rather than a laggard in the pursuit of a fairer world.

An agreed upon definition of oral health justice challenges the profession to move beyond charity and outreach models toward sustainable, community-led solutions. It calls for a redistribution of power—where patients are not passive recipients but active partners in care. The future of oral healthcare depends on a reimagined professionalism—one that is courageous, inclusive, and justice-driven. Defining and pursuing oral health justice is not optional; it is essential. It is the compass that can guide the profession through the complexities of the 21st century and ensure that every smile, regardless of zip code or background, has a chance to shine.

References

- Peres, M. A., Macpherson, L. M., Weyant, R. J., Daly, B., Venturelli, R., Mathur, M. R., ... & Watt, R. G. (2019). Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. The Lancet, 394(10194), 249-260.

- Smith, CS, Stilianoudakis, SC, Carrico, CK. Professionalism and professional identity formation in dental students: Revisiting the professional role orientation inventory (PROI). J Dent Educ. 2022; 1- 8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.13159

- Razack, S., de Carvalho Filho, M. A., Merlo, G., Agbor-Baiyee, W., de Groot, J., & Reynolds, P. P. (2022). Privilege, social justice and the goals of medicine: Towards a critically conscious professionalism of solidarity. Perspectives on medical education, 11(2), 67-69.

- Thurston, M. M., & Hammer, D. (2022). Well-being may be the missing component of professionalism in pharmacy education. American journal of pharmaceutical education, 86(5), 8808.

- Johnson, T., Williams, K., Marussinszky, N., & Felix-Faure, A. (2023). Wellbeing and professionalism. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech-Language Pathology, 25(2), 38-41.

- Smith CS, Razack S, Reynolds P. (2025) Advocating for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice: A Reimagined Professionalism In: Harter TD, Merlo G (eds) Medical Professionalism Theory, Education, and Practice. Oxford University Press https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780197640814.003.0033

- American College of Dentists Ethics Report: The new professionalism. Georgetown University Press; 2020.

- Fleming, E., Smith, C. S., & Quiñonez, C. R. (2023). Centring anti‐oppressive justice: Re‐envisioning dentistry's social contract. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 51(4), 609-614.

- Zaidi Z, Razack S, Kumagai AK. Professionalism revisited during the pandemics of our time: COVID-19 and racism. Perspectives on Medical Education. 2021;10(4):238-244.

- Smith, CS , & Simon, LE (2024). To do good and refrain from harm: Combating racism as an ethical and professional duty. The Journal of the American Dental Association. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2024.08.003

Dr. Smith is a board member of the Academy for Professionalism in Health Care and the current president of the American Society for Dental Ethics.

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Dental Profession Must and Can be the Signal to MAHA’s Noise on Water Fluoridation

By: Nanette Elster, JD, MPH

|

Recently, some of the greatest public health achievements of the 20th century have come under attack by the current administration in its so-called effort to “Make America Healthy Again,” (MAHA). One of those achievements which has been most virulently attacked in recent months is community water fluoridation. Based on flawed rationales and outright misinformation, public mistrust and distrust is being fueled. The flames of misinformation are being blamed by those legislators responding in lockstep with the MAHA agenda, and ignoring the expertise of trained professionals.

To date, two states, Utah and Florida have already banned community water fluoridation and several additional states have proposed legislation to restrict the use of fluoride, despite demonstrable evidence of the benefits of such programs as well as the anticipated risks of their discontinuation. A recent study looking at eliminating community water fluoridation by Choi and Simon, “projects an increase in tooth decay among children of 7.5 pp and costs of approximately $9.8 billion over 5 years.” Such an enormous financial and human cost seems unjust, if not outright harmful, given that the overwhelming scientific evidence suggests that the current level of fluoride in community water is a safe and an effective tool for preventing tooth decay, particularly in underserved communities. MAHA’s stance on water fluoridation and the resultant legislative action by some states is in direct contravention of the professional expertise of dentists, necessitating action by oral health professionals to combat misinformation and to continue to assert their expertise in fulfillment of their ethical obligation to “have the benefit of the patient as their primary goal.”

Kessler and Rosato, President and President-elect of the American Dental Association, respectively, recognizing the professional and ethical obligations of dentists, wrote in the Journal of the American Dental Association that: “The profession has a responsibility to speak up, communicate the science, and educate policy makers and the public about community water fluoridation and other oral health issues.” As professionals, dentists are obligated to adhere to the social contract. This is made clear in the ADA Principles of Ethics & Code of Professional Conduct (the Code). The Introduction states that: “The dental profession holds a special position of trust within society. As a consequence, society affords the profession certain privileges that are not available to members of the public-at-large. In return, the profession makes a commitment to society that its members will adhere to high ethical standards of conduct.” In addition, the Code obligates dentists to: “refrain from harming patients,” “use their skills, knowledge and experience for the improvement of the health of the public,” “actively seek allies throughout society on specific activities that will help improve access to care for all. . .” and “communicate truthfully.”

What makes the assertion of one’s professional obligations and adherence to the core tenets of ethics so complicated is the rejection of their expertise (their specialized skills and knowledge) by those in positions of power and authority. Expertise is fundamental to what makes a profession a profession. In the 3rd Edition of the Encyclopedia of Bioethics, Ozar, a philosopher and renowned expert in dental ethics, asserts that, “the practice of specialized expertise and the special moral commitments associated with professional practice are what differentiate a profession from other occupations.” Ozar goes on to explain that “only persons fully educated in both knowledge and practice of a profession’s expertise can be relied on to judge correctly the need for expert intervention in a given situation or to judge the quality of such intervention as it is being carried out.”

Additionally, true expertise evolves and changes over time as new information, new technologies, and new applications become available. Pilkington, Caplan and Parsi acknowledge the importance of this flexibility and nimbleness asserting that, “Public health relies on experts who may change recommendations as evidence emerges. Furthermore, complex problems call for an array of experts, each of whom should provide evidence-based recommendations consistent with their subject matter expertise, education, and experience.” To be able to pivot and interpret new information as it becomes available as well as to evaluate the risks and benefits of continuing community water fluoridation, dentists seem in possession of the most trustworthy and accurate information.

Community water fluoridation is complex and necessitates, among other things, a deep understanding of scientific evidence, quality control measures and delivery mechanisms. And, as with any research intervention, demonstrable effectiveness must outweigh harm. When it comes to community water fluoridation, dentistry is the profession on which the public should rely in assessing the necessity and quality of such intervention. Dentists, with their education, training, and commitment to the social contract, must be the signal to drown out the noise.

Nanette Elster is a Professor at the Neiswanger Institute for Bioethics, Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine.

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Swick Exercise:

Part 3A: Ranking Data Results: Wave 1

By: Frederic W. Hafferty, PhD

|

Background

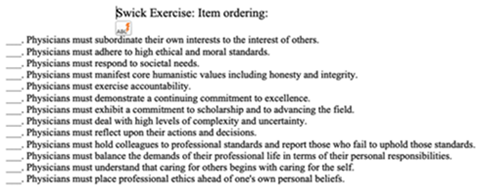

The Swick Exercise has been used, with various audiences, for 20+-years. The exercise has two sections. The first contains a 13-item list anchored by Swick’s core list of 10 professionalism behaviors augmented with three additional items suggested by Ed Hundert. The item list replicates the ordering of Swick’s 2002 article1 to which the three “Hundert” items were added on in the order Ed thought of them. This was to be a class exercise, not a study and therefore issues of instrument design or item validity were not part of any discussions. For the exercise itself, respondents were asked to do a forced ranking (1-13) as to “how important” they saw each “in terms being a good physician,” but with the directed object – “a good physician” – subject to change depending on the audience (e.g., nursing, a specific specialty group, etc.). Respondents also were told that since the ranking was forced, items ranked lower were not to be thought of as unimportant, but rather “simply” not as relatively important as those they ranked higher. In the Exercise’s second section, respondents were asked to select one of the 13 statements “you have trouble accepting (your choice)” and to “reword/edit/rewrite it so that you would feel comfortable committing to it as a core professional principle.”

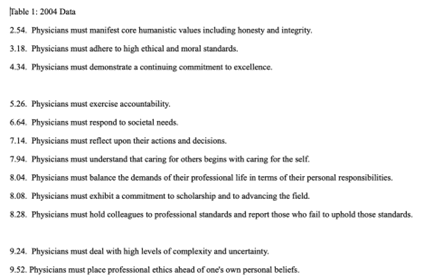

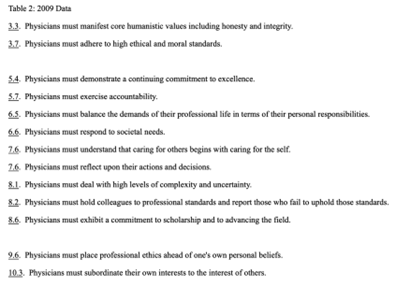

Below are ranking data from two different first year medical school classes. The actual mean rankings shown below – to the 10th for the 2004 exercise and 100th for the 2009 – are what students received and are reproduced here unchanged.

Ranking Results

Table 1 data is from a 2004 exercise at 2 school whose stated mission is to train future rural family physicians. Table 2 data is from a 2009 exercise at a school whose graduates typically match into sub-specialty (non-primary care) career tracks. Both have similar class sizes (small), and both exercises took place during the first month of school. Class discussions followed both the exercise itself, and also in the subsequent class after students received their class ranking and rewrite data. I chose these two schools to capture possible differences in terms of time (2004 versus 2009), but also to illustrate what I came to see over the years of doing this exercise as some “enduring patterns” in both the ranking and rewrite data. I provided students with their ranking data in a variety of formats (one of which appears below). Rewrite data was unedited and thematically grouped by question. Typically, students tend to rank more items lower (mean scores between 6.5-13: N=9) than higher (mean scores between 1-6: N=4). Longer story short, what appears below in both tables is exactly what students saw as one part of the overall ranking results.

Some (all too) Brief Observations

There is a lot to unpack across these two rankings, and given space limitations, I will restrict my comments to Swick’s “lead six” items: (a) altruism; (b) ethical and moral standards; (c) societal needs; (d) humanistic values including honesty and integrity; (e) accountability (general); and (f) excellence. Three of these – ethical and moral standards, humanistic values, and excellence – were “high fliers” in both sets of rankings – something generally true for most of the Swick exercises I have done. Swick’s general accountability item also ranked highly for both groups, perhaps reflecting its more moderately sounding “societal needs” language than the much lower ranked (10th for both groups with almost identical mean ranking: 8.28 versus 8.2) self-regulatory call to hold colleagues to professional standards and report those who fail to uphold those standards. The final and most striking finding, at least for me, was the “fall” of Swick’s altruism item (“Physicians must subordinate their own interests to the interest of others”) from its lead placement in Swick’s original list to a precipitous last place ranking by students. This “fall from grace” is as close a universal finding across all Swick exercises, regardless of medical student population, as well as all nursing and physician-clinician groups. The only “deviation” from this 99%-of-the-time-last-place ranking (and always with a 9 and sometimes a 10+ mean score) came with two groups: (1) minority pathway/pipeline program college students (multiple times), and (2) a one-time exercise with a group of “health care experts” where MDs were a minority presence – with both giving Swick’s altruism item more of a middle-of-the-pack ranking.

These above ranking results, along with others I will cover in our next installment of this series, highlight what I feel is the fundamental revelation in these data. Medical student equivocations about professionalism and what it means to be a good doctor are substantive, nuanced, and most importantly, long standing. As noted in my introduction to this series, I created the Swick exercise because of still earlier (1990s) concerns about how my students seemed to push back against the word “professionalism” along with related calls to altruism and selfless service. Perhaps today’s medical students, residents, fellows and practitioners hold different beliefs and value sets around what it means to be a good physician – but I do not think so. Instead, the picture appears even more contested and toxic2 with ever expanding concerns over physician burnout, well-being, and work-life balance.3 Given that I no longer work directly with medical students, I have no direct way of knowing whether my suspicions are true or not, but if you are so inclined, please feel free to use the exercise. I would love to learn what you find.

Next: Part 3B: Ranking Data Results: Wave 2

REFERENCES

1. Swick, Herbert M. 2000. Toward a Normative Definition of Medical Professionalism. Acad Med 75 612-16.

2. Fuse Brown, Erin C. 2025. Defining Health Care “corporatization”. NEJM 393 (1): 1-3.

3. Shanafelt, Tait D, Colin P West, Christine Sinsky, Mickey Trockel, Michael Tutty, Hanhan Wang, Lindsey E Carlasare, and Liselotte N Dyrbye. 2025. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction with Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General Us Working Population Between 2011 and 2023. Mayo Clin Proc 100 (7): 1142-58.

Frederic W. Hafferty, PhD is a medical sociologist and Senior Fellow, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Back to Table of Contents

|

APHC Roundtable

Friday, September 12 at 3 p.m. ET

|

From Framework to Practice: University Health's Journey to Trauma-Informed Care Certification with Sarah Sebton

This interactive discussion will cover:

- How the trauma-informed healthcare certification process works locally, adapted for healthcare settings using the Institute for Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care’s Organizational Change Manual

- Main challenges and successes, including - creating safe and supportive environments, workforce training, policy alignment, and staff support

- How University Health has moved into the sustainability phase, continuing to use trauma-informed principles in everyday practice

Register at: https://bit.ly/APHCRoundtables

Sarah A. Sebton is the Executive Director of Behavioral Health and Trauma-Informed Care at University Health, South Texas' largest public health system and safety-net academic medical center. In this role, she leads operations of the Behavioral Health service line, both inpatient and outpatient, as well as University Health’s internal activities as a trauma-informed organization, which include staff training, policy change, and system-wide projects that acknowledge the impact of trauma while creating safe and supportive environments that promote healing. Sarah’s leadership was pivotal in earning University Health’s Level 1 trauma-informed care certification in October 2024, making it the first health system in the country to receive any type of official trauma-informed care designation.

Sarah holds a Masters of Public Health (MPH) and Masters of Public Administration (MPA) from New York University (NYU). She has worked for many nonprofit and government entities in her career, including The Health Federation of Philadelphia, Smile Train, Mount Sinai Health System, and the Travis County Healthcare District in Austin, TX. Sarah also served as a Public Health and Wellness Officer in the Texas State Guard for over four years and is an adjoint faculty member at UT Health San Antonio School of Medicine. Her ongoing efforts focus on staff wellness and resilience, trauma awareness, trauma-informed communication, and the intersections between trauma and public health. Outside of her work, Sarah is a proud rabbit and dog mom, is in training to become a sommelier, and volunteers at a conservation park caring for rhinos and giraffes

Roundtables are for APHC Members only.

Check out our membership benefits here.

Join APHC to access previous Roundtable recordings.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Healthcare Professionalism: Education, Research & Resources Podcast

|

Professional Formation and APHC collaborate on a podcast, Healthcare Professionalism: Education, Research & Resources.

Over 125 podcast episodes have been released with over 17,000 downloads.

Released every other Saturday morning, recent episodes include Rachel Pittmann discussing Telehealth Etiquette and Amal Khidir talking about Designing the Faculty Development Professionalism Program with Multi-cultural Perspectives.

You can access the podcast episodes on your favorite platform or at: https://bit.ly/PF-APHC-Podcast

Back to Table of Contents

|

APHC Member Announcements

|

Bryan Pilkington, PhD published his book The Medical Act: Conscientious Practice in a World of Dissention and Disagreement.

If you are an APHC member, we will publicize your events, job searches, research, grants, articles, podcasts, books, etc., in the newsletter.

Back to Table of Contents

|

As a member, you have access to special benefits that include:

- Belonging to a community of like-minded professionals

- Participating in the monthly Professionalism Education

Roundtables with authors, faculty, and researchers, plus accessing past recordings

- Accessing 15 Professional Formation modules for individuals for free

- Enrolling in the APHC Faculty Development Certificate program known as LEEP (Leadership Excellence in Educating for Professionalism), which was launched in 2020 and offers longitudinal mentoring for a select group of

individuals seeking to deepen their knowledge and skills in

professionalism education, assessment, and research

- Posting your research, articles, podcasts, webinars, conferences, and books in the newsletter distributed to about 15,000 people

- Receiving a 20% discount on educational videos created by the Medical Professionalism Project, which also allows you to obtain MOC and CME

- Registering for APHC conferences with discounts

- Participating in APHC committees, which include the conference program, membership, and education committees

Our annual membership fees are very inexpensive and are valid for one year from the payment date. Select from seven types of membership, including the institutional membership for four people. See the descriptions.

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Academy Newsletter Editors

|

Editor-in-Chief: Bryan Pilkington | Managing Editor: Yvonne Kriss

Please contact Yvonne if you'd like to contribute an article to this newsletter.

If you know someone who would benefit from reading Professional Formation Update, please pass this along. They can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here.

|

Academy for Professionalism in Health Care

PO Box 20031 | Scranton, PA 18502

|

Follow us on social media.

|

|