Volume 8, Issue 9 - October 2025

|

Professionalism: Pressing Issues and Potential Responses

By: Bryan Pilkington, PhD

|

Our October issue houses reflections on pressing issues in healthcare professionalism and the potential responses for these issues. The first article, “The Humanities & Professionalism in Medical Education: A Symbiosis That Works,” approaches considerations of healthcare professionalism through reflection on the importance of humanities. What would have seemed an obvious connection some years ago is being revived and work by the author, Mary Horton, and others, has highlighted the benefits of the humanities for health professionalism. This excellent piece ties in themes of both medicine and of those rooted in issues of our shared humanity. It is followed by another excellent piece on a pressing public health and professionalism issue. That second article, authored by Scott Tomar, “Ethics and Dental Public Health: The Case for Community Water Fluoridation,” picks up on themes explored in the September issue of The Academy. The third article of this issue is the next installment of Fred Hafferty’s Swick Test series.

For those who have taken an interest in the Swick ongoing series or who have questions about the Swick Test, connections between professionalism and the humanities, or the need for strong stands by professionals in the face of emerging public health crises, do write to us. We have begun to receive letters to the editor and will begin to publish such letters in a forthcoming section of The Academy, aptly titled “Letters to the Editor.” Look out for this section in future issues and we look forward to this new way to continue our conversations on healthcare professionalism.

The issue concludes with the usual announcements from members, reminders about roundtables, and other healthcare professionalism-related news.

Bryan Pilkington, PhD, is Professor of Bioethics, in the Department of Medical Sciences, at Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine, and the Editor-in-Chief of The Academy: A Forum for Conversations about Health Care Professionalism.

|

The Academy for Professionalism in Health Care Virtual Conference

|

Professionalism in a Time of Change

“The only constant in life is change.” – Heraclitus, c. 500 BC

Change can be inspiring—or intimidating. In healthcare, where professionalism is shaped by core values and evolving expectations, how we prepare for, manage, and adapt to change is critical. New challenges may spark innovation and growth—or lead to burnout and decline.

Join us for the Academy for Professionalism in Healthcare’s International Virtual Conference, where we’ll explore what professionalism looks like in times of change—at the individual, team, institutional, national, and global levels.

📆 When: Wednesday, November 12 & Thursday, November 13, 2025, 8:00 AM – 1:00 PM ET (both days)

📍 Where: Zoom

What to Expect:

-

40+ Highly interactive Sessions including:

-

How-to Workshops

-

Problem-Solving Sessions

-

Panel Discussions

- Roundtables

- Games

- Oral Presentations

- Flash Presentations

-

Keynote on Theories and Research Related to Change and Change Management

-

Symposium to explore Change in Different Contexts

💻 Can’t make it live? All sessions will be recorded and available on demand.

🤝 Plus: Plenty of opportunities to connect and network with peers from around the world.

Don’t miss this dynamic, inclusive event that brings together healthcare professionals and trainees from all disciplines.

👉 [Click here to register now]

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Humanities & Professionalism in Medical Education: A Symbiosis That Works

By: Mary E. Kollmer Horton, M.P.H., M.A., Ph.D.

|

The inclusion of the humanities in medical education has a contentious history in American medicine across the twentieth century. Few argue the irrelevance of the humanities to medicine or its training, yet the value is hard to quantify, and the challenge of time, particularly curricular time, lingers. In the 1970s, Human Values training through the Institute on Human Values in Medicine (IHVM) of the Society for Health and Human Values grounded its various training programs in disciplinary humanities. The work of the Institute dramatically increased the number of U.S. health professions schools teaching such content, but never achieved the goal of standard inclusion by accrediting organizations (Pellegrino; McElhinney). In comparison, professionalism, a concept largely developed and examined by sociologists during the same time period, was operationalized by medical educators in the 1990s and quickly moved forward into the American medical curriculum (Stobo and Blank; Colleges; Hafferty and Castellani). In examining medical professionalism, as conceived within medicine, its use is to foster skills within clinicians which mirror what was hoped humanities education would achieve: improved communication, ethical and moral reasoning, altruism, accountability, and lifelong learning (Stern; Swick). Professionalism was adopted by medicine at a time of need to humanize medicine in ways that the humanities alone could not.

Hafferty and Castellani (2011) describe how both sociology and medicine have an interesting relationship with professionalism; both are interested, but with different timing and purpose. In Hafferty and Castellani’s words, they are “Two Cultures: Two Ships” sailing at different times, in different directions, for different purposes. Sociologists of the mid twentieth century were analyzing, theorizing, and defining the professions, the structure of organizations, the influences of social forces, and examining the growth of the medical profession and its transformation into a multifaceted research, business, and corporate enterprise (Starr; Freidson). Medicine, grappling with the mid to late 20th century and these many non-humanistic forces, strove to bring humanity back into its education and practice. In the 1970’s the IHVM looked to the humanities to do this, but success was limited. Bickel, at the cusp of the 21st century, brings forward the thoughts of sociologists that describe medical education as sitting within a much larger corporate environment, fed by many external forces, many of which are not patient-focused (Wear)(p.184). The humanities do not fit within this business, technology-driven culture. By the 1990s, medicine, in its continued search to right its ship and counter such forces, found in professionalism a language able and culturally acceptable to refocus medicine on the patient and its commitment to society (Stobo and Blank). The Project to Rebalance and Integrate Medical Education (PRIME) in the 2000s highlighted the humanities' connection within professionalism. Focusing on ‘rebalancing’ the medical curriculum with humanities through professionalism, noting professionalism as “intrinsically scientific, clinical, ethical, and social.” (Doukas) (p. 334). Professionalism, with its grounding in organizations, structure, work, communication, and behaviors, was culturally more acceptable to the medical enterprise. Sitting within professionalism, symbiotically, the humanities could make an acceptable home.

Historian Brian Dolan (2015) reflects on the changing use of the humanities in medical education across the twentieth century, which offers a propitious nod to professionalism. Dolan states that in the early part of the century, when medicine was professionalizing, a liberal arts education, or one grounded in the humanities, represented a well-educated professional individual. By the mid-century, medical education was increasingly focused on the growing amount of science and technology, at the loss of humanities content. The call for the humanities in the medical curriculum in the 1960s and 70s, according to Dolan and others, was to address the moral problems that science and technology had created in medicine. By the late century, Dolan states that medical educators were increasingly looking toward the humanities for the building of moral character. Clinical ethics, as adopted into medical education in the 1980s, teaches a way of thinking through moral dilemmas, professionalism teaches a way of behaving grounded in an understanding of social responsibility, communication, and a variety of other skills that the humanities are hoped to foster (Dolan). Dolan’s reflections on the use of humanities in medical education are consistent with other prominent voices. Delese Wear uses sociologist Renee Fox‘s sentiments to describe professionalism as a remaking of past principles and practices, all of which have long been an expectation of a humanist physician (Wear)(p.xi-xii). Such humanistic content under the banner of professionalism culturally fits and works to forward the goal of fostering humanism. In a kind of symbiosis, the humanities sit under the wings of professionalism, an applied field developed by medicine, for medicine, acceptable to medicine. It’s been said that medicine saved ethics from being a lost esoteric field of philosophy (Toulmin). Let us consider whether professionalism in medicine may be giving a similar new life to the humanities.

References

- Colleges, Association of American Medical. Medical School Learning Objectives Project for Medical Student Education: Guidelines for Medical Schools. Washinging DC.: Association of American Medical Colleges, 1998. Print.

- Dolan, Brian, ed. Humanitas: Readings in the Development of the Medical Humanities. San Francisco, California: University of California Medical Humanities Press, 2015. Print.

- Doukas, David J., Laurence B. McCullough, Stephen Wear for the Project to Rebalance and Integrate Medical Education (PRIME) Investigators. "Medical Education in Medical Ethics and Humanities as the Foundation for Developing Medical Professionalism." Academic Medicine 87 (2012): 334-41. Print.

- Freidson, Eliot. Professionalism: The Third Logic. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2001. Print.

- Hafferty, Frederic W., and Brian Castellani. "Two Cultures: Two Ships: The Rise of a Professionalism Movement within Modern Medicine and Medical Sociology’s Disappearance from the Professionalism Debate." Handbook of the Sociology of Health, Illness, and Healing: A Blueprint for the 21st Century. Eds. Pescosolido, Bernice A., et al. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2011. 201-19. Print.

- McElhinney, Thomas K., Edmund D. Pellegrino. "The Institute on Human Values in Medicine: Its Role and Influence in the Conception and Evolution of Bioethics." Theoretical Medicine 22.4 (2001): 291-317. Print.

- Pellegrino, Edmund D, Thomas K. McElhinney. Teaching Ethics, the Humanities, and Human Values in Medical Schools: A Ten Year Overview. Washington D.C.: Institute on Human Values in Medicine, 1982. Print.

- Starr, Paul. The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers, 1982. Print.

- Stern, David Thomas. Measuring Medical Professionalism. Oxford Scholarship Online. 1st ed. ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. Print.

- Stobo, John D., and Linda L. Blank. "Project Professionalism: Staying Ahead of the Wave." The American journal of medicine 97.6 (1994): i-iii. Print.

- Swick, Herbert M. "Toward a Normative Definition of Medical Professionalism." Academic Medicine 75.6 (2000): 612-16. Print.

- Toulmin, Stephen. "How Medicine Saved the Life of Ethics." Perspectives in biology and medicine 25.4 (1982): 736-50. Print.

- Wear, Delese, Janet Bickel, ed. Educating for Professionalism: Creating a Culture of Humanism in Medical Education. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2000. Print.

Mary Horton is has been an active member of the APHC since 2017. She directs the Medical Student Research Office, is instructional faculty for the Office of Educational Programs, and the McGovern Center for Humanities and Ethics at the McGovern Medical School of UTHealth Houston. Trained as an interdisciplinary humanities scholar, she writes and teaches on the history of American Medical Education and its relationship to the humanities. Additional interests include the history of American psychiatric and geriatric care.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Ethics and Dental Public Health: The Case for Community Water Fluoridation

By: Scott L. Tomar, DMD, DrPH

|

Dental Public Health has long supported community water fluoridation (CWF), a public health measure to reduce the incidence of dental caries (tooth decay) that has been in use for about 80 years and reaches about 400 million people worldwide. Challenges to the practice of CWF are as old as CWF itself, although strong opposition was traditionally limited to small but vocal groups. Recent years have seen increased questioning of the safety, effectiveness, and appropriateness of CWF, amplified substantially by the current federal administration (1) during a time of strong political polarization in trust in government health agencies (2). This is an opportune time to apply public health ethical analysis to CWF.

The most widely recognized Public Health Code of Ethics was developed by the American Public Health Association in 2019 (3). That Code defined the foundational values of public health and was intended to guide individual and collective decision making by public health practitioners and institutions. It provides a set of considerations for use in decision-making process to ensure that authority and power in public health are exercised in fair and productive manner. As described in the Public Health Code of Ethics, ethical analysis of proposed public health action involves four components:

- Determination of the public health goals of the proposed action.

- Identification of ethically relevant facts and uncertainties.

- Analysis of meaning and implications of proposed action for health and rights of affected individuals and communities.

- Analysis of how the proposed action fits with core public health values.

This paper applies those components to the public health measure of CWF.

Determination of the public health goals of proposed action. The primary objective of CWF is to reduce the incidence of dental caries, a disease that remains the most common chronic disease in the United States (4). Because dental caries is a multifactorial disease that involves diet, personal oral hygiene, quality and quantity of saliva flow, and other factors, CWF has never been expected to completely prevent the disease. Rather, the intent is to reduce the incidence rate and severity of the disease in populations. The secondary objective of CWF is to reduce socioeconomic disparities in dental caries prevalence.

Identification of ethically relevant facts and uncertainties. The effectiveness of CWF for reducing the incidence of dental caries has been widely upheld since the pioneering trials that began in the 1940s (5). At least nine high quality systematic reviews published in the past 25 years, including those commissioned by government health ministries, have concluded that CWF is effective in reducing dental caries rates, with about a 25–30% reduction in the incidence of new caries lesions (6-14). Contemporary studies conducted across multiple countries remain remarkably consistent in showing a lower disease burden in fluoridated communities compared with sociodemographically similar but non-fluoridated communities. U.S. nationally representative data indicate that CWF reduces income-related disparities in dental caries (15).

The primary uncertainties around CWF involve claims of adverse health effects. Accusations of harms began in the earliest days of CWF and have included a veritable laundry list of supposed disease risks, including various cancers, immunosuppression, thyroid dysfunction, bone fractures, Down syndrome, allergic reactions, infertility, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, kidney disease, and many others, but these have all been scientifically refuted (16). The latest accusation is that CWF affects children’s neurodevelopment and lowers their IQ, but the overwhelming majority of evidence supposedly showing a link between fluoride exposure and IQ were low quality studies conducted in endemic fluorosis regions of China, India, or Iran (17). Such regions have levels of fluoride exposure many times greater than those associated with CWF, and many of the studies also did not account for exposure to heavy metals in the water sources and the many toxins associated with indoor coal burning. The best available evidence indicates that levels of fluoride exposure comparable to those used in CWF are not associated with any change in IQ or neurodevelopment (18). To date, the only documented adverse effect of CWF is mild enamel fluorosis, a change in the appearance of dental enamel generally not readily apparent to the affected individual or casual observer, has no effect on tooth function, and is associated with greater caries resistance (19).

Analysis of meaning and implications of proposed action for health and rights of affected individuals and communities. All public health measures involve a balance between benefits and risks. On the benefits side, there is about 80 years of consistent evidence that CWF reduces the incidence of dental caries. Other than mild fluorosis, the best available evidence indicates that there are no known health risks associated with CWF. That is why CWF continues to be supported by most major public health organizations, including the American Public Health Association (20) and the World Health Organization (21).

Public health also involves a balance between the rights of individuals and the health of the population, including those most vulnerable to disease. The practice of CWF is analogous to other public health measures that involve the addition of trace minerals or vitamins to widely consumed products to prevent disease, such as the fortification of milk with Vitamin D to promote bone health, addition of folic acid to grain and cereal products to prevent neural tube defects, and the addition of iodine to salt to prevent iodine deficiency and boost thyroid function.

Communities and individuals who do not wish to receive CWF have multiple avenues to avoid it. CWF is primarily a local issue in the United States, and communities can choose to not have CWF either through direct public votes or, more commonly, through the decisions of county or local elected officials. As has been demonstrated by recent actions in Utah and Florida, state legislatures are able to pass legislation to stop CWF. Individuals who do not wish to receive fluoridated water but reside in a fluoridated community have multiple options, including the installation of water filtration systems that remove fluoride and other minerals or using non-fluoridated bottled water for drinking and food preparation.

Analysis of how the proposed action fits with core public health values. The core public health values described in the Public Health Code of Ethics include Professionalism and Trust; Health and Safety; Health Justice and Equity; Interdependence and Solidarity; Human Rights and Civil Liberties; Inclusivity and Engagement. The decision of communities to initiate or maintain CWF is consistent with all these core values.

Professionalism and Trust. The practice of CWF is based on evidence of safety and effectiveness that is not influenced by secondary interests. In fact, under the predominant reimbursement model in the United States, dentistry would stand to financially benefit much more from not preventing dental caries through the use of CWF.

Health and Safety. When implemented as recommended by public health authorities, CWF prevents, minimizes, and mitigates health harms and promotes and protects public safety, health, and well-being. Evidence from Calgary’s cessation of CWF indicates that it led to an increase in caries prevalence and treatment costs (22), so stopping CWF likely increases harms to the public.

Health Justice and Equity. CWF is perhaps the most equitable approach to preventing dental caries because it reaches all members of the community regardless of their socioeconomic status, health literacy, or ability to access services.

Interdependence and Solidarity. As described in the Code, public health practitioners and organizations have an ethical obligation to foster positive—and mitigate negative—relationships among individuals, societies, and environments in ways that protect and promote the flourishing of humans, communities, nonhuman animals, and the ecologies in which they live. In view of the tremendous influence of oral health status on social functioning and the role of CWF in reducing the incidence of oral disease, CWF is compatible with this core public health value.

Human Rights and Civil Liberties. Although most Americans support the provision of CWF (23), individuals who wish to avoid it have multiple options to do so.

Inclusivity and Engagement. As noted earlier, CWF in the United States is primarily a local issue. Decisions to initiate or maintain CWF nearly always involve forums and public hearings at which the rationale is presented, and community members can engage. It is ultimately a community decision on whether to initiate or maintain CWF.

In summary, the public health practice of community water fluoridation is not only effective for reducing the burden of dental caries but is consistent with the Code of Public Health Ethics. While professional ethics demand that we continuously update the science base supporting this public health measure, we also must be vigilant in countering misinformation that would deny its preventive benefits to millions of people.

References

- Nunn EB. Kennedy Calls for States to Ban Fluoridated Drinking Water. New York Times. April 7, 2025.

- Kearney A, Sparks G, Hamel L, Montalvo JI, Valdes I, Kirzinger A. KFF Tracking Poll on Health Information and Trust: January 2025. San Francisco, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2025.Available from: https://www.kff.org/health-information-trust/kff-tracking-poll-on-health-information-and-trust-january-2025/.

- American Public Health Association. Public Health Code of Ethics Wasington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2019. Available from: https://www.apha.org/getcontentasset/43d5fdee-4ccd-427d-90db-b1d585c880b0/7ca0dc9d-611d-46e2-9fd3-26a4c03ddcbb/code_of_ethics.pdf?language=en.

- National Institutes of Health. Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges. . Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2021. Available from: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2024-08/oral-health-in-america-advances-and-challenges-full-report.pdf.

- Ast DB, Fitzgerald B. Effectiveness of water fluoridation. J Am Dent Assoc. 1962;65:581-7.

- McDonagh MS, Whiting PF, Wilson PM, Sutton AJ, Chestnutt I, Cooper J, et al. Systematic review of water fluoridation. BMJ. 2000;321(7265):855-9.

- Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Dental Caries (Cavities): Community Water Fluoridation. Atlanta, GA; 2013 [updated 2017]. Available from: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/dental-caries-cavities-community-water-fluoridation.html.

- Eason C, Elwood JM, Seymour G, Thompson WM, Wilson N. Health effects of water fluoridation: a review of the scientific evidence. Auckland and Wellington, NZ: Royal Society of New Zealand and Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor; 2014.Available from: https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/assets/documents/Health-effects-of-water-fluoridation-Aug-2014-corrected-Jan-2015.pdf.

- Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Walsh T, Lewis SR, Riley P, Boyers D, Clarkson JE, et al. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2024;10(10):Cd010856.

- Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Worthington HV, Walsh T, O'Malley L, Clarkson JE, Macey R, et al. Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(6):Cd010856.

- Sutton M, Kiersey R, Farragher L, Long J. Health effects of water fluoridation: an evidence review. Dublin: Health Research Board; 2015.Available from: https://www.hrb.ie/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Health_Effects_of_Water_Fluoridation.pdf.

- Jack B, Ayson M, Lewis S, Irving A, Agresta B, Ko H, et al. Health Effects of Water Fluoridation: Evidence Evaluation Report, report to the National Health and Medical Research Council. Canberra, Australia: NHMRC Clinical Trials Centre, The University of Sydney; 2016.Available from: https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/reports/fluoridation-evidence.pdf.

- Belotti L, Frazão P. Effectiveness of water fluoridation in an upper-middle-income country: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2022;32(4):503-13.

- Sharma V, Crowe M, Cassetti O, Winning L, O'Sullivan A, O'Sullivan M. Dental caries in children in Ireland: A systematic review. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2024;52(1):24-38.

- Sanders AE, Grider WB, Maas WR, Curiel JA, Slade GD. Association Between Water Fluoridation and Income-Related Dental Caries of US Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(3):288-90.

- American Dental A. Fluoridation Facts. Chicago: American Dental Association; 2025. Available from: https://www.ada.org/resources/community-initiatives/fluoride-in-water/fluoridation-facts.

- National Toxicology Program. NTP monograph on the state of the science concerning fluoride exposure and neurodevelopment and cognition: a systematic review. 2024 Aug. Report No.: 2330-1279 (Print) Contract No.: 8. Available from: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2024-08/fluoride_final_508.pdf

- Kumar JV, Moss ME, Liu H, Fisher-Owens S. Association between low fluoride exposure and children's intelligence: a meta-analysis relevant to community water fluoridation. Public Health. 2023;219:73-84.

- Iida H, Kumar JV. The association between enamel fluorosis and dental caries in U.S. schoolchildren. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140(7):855-62.

- American Public Health Association. Community Water Fluoridation in the United States. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2008. Available from: https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/24/13/36/community-water-fluoridation-in-the-united-states.

- Petersen PE, Ogawa H. Prevention of dental caries through the use of fluoride--the WHO approach. Community Dent Health. 2016;33(2):66-8.

- McLaren L, Patterson SK, Faris P, Chen G, Thawer S, Figueiredo R, et al. Fluoridation cessation and children's dental caries: A 7-year follow-up evaluation of Grade 2 schoolchildren in Calgary and Edmonton, Canada. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2022;50(5):391-403.

- CareQuest Institute for Oral Health. Community Water Fluoridation National Opinion Poll Results. Boston, MA: CareQuest Institute for Oral Health; 2025. Available from: https://www.carequest.org/resource-library/community-water-fluoridation-national-opinion-poll-results.

Dr. Tomar is Associate Dean for Prevention and Pubic Health Sciences at UIC College of Dentistry and serves as spokesperson on community water fluoridation for the American Dental Association. He is a diplomate of the American Board of Dental Public Health.

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Swick Exercise:

Part 3B: Ranking Data Results: Wave 2

By: Frederic W. Hafferty, PhD

|

Background

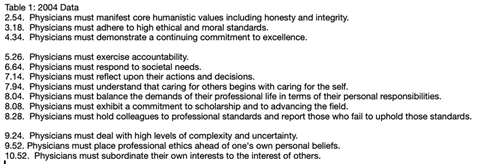

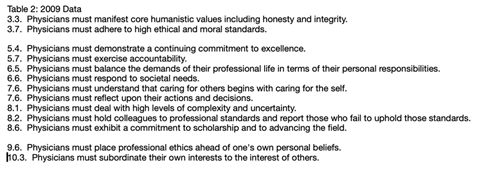

Last time, in Part 3A: Ranking Data Results Wave 1, we covered a quick overview of the exercise itself, the core 10 items from Swick’s 2002 article,1 the additional three items suggested by Ed Hundert, the two different sections in the exercise itself (ranking and rewriting), and an all-to-brief overview of some findings illustrated across two (2004 versus 2009) administrations of the exercise at two different medical schools. In this previous posting, we focused on Swick’s “lead six” items and found that three of these items – ethical and moral standards, humanistic values, and excellence – were “high fliers” in both sets of rankings. Alternatively, Swick’s altruism item (“Physicians must subordinate their own interests to the interest of others”) suffered a different fate as it “fell” from its “first place” in Swick’s original list to a last place ranking by students. Moreover, this “fall from grace” is as close to a universal finding across all 20+ years of using this discussion tool. regardless of the group, including multiple medical student, nursing and physician-clinician groups.

Additional Ranking Results

Here, and circling back to issues of values, standards, and excellence, while it appears that first-month first year, medical students come to medical school with relatively unencumbered views about the importance of humanistic values, ethics/moral standards, and commitment to excellence to being a good doctor, they alternatively found the call to selfless service (Swick’s altruism item) along with the call to prioritize professional ethics over personal values (Item #13 on the ranking list – and one of the three items suggested by Hundert) to be more troubling and contestable. Given these latter reservations, it may come as no surprise that Swick’s altruism item and Hundert’s ethics-over-personal-beliefs tension (here and in other exercises) are the items most often chosen to be rewritten in the second part of the exercise, and something we will cover in our next Newsletter posting as students sought to make the various Swick Exercise items more “commitment friendly” within their emergent understandings of what it means to be a good doctor.

There are other key tensions within the overall Swick Exercise data as well. One is between Swick’s generic call to high ethical and moral standards (with rankings of 3.18 - Table 1 and 3.7 - Table 2) versus Hundert’s “challenge” to “place professional ethics ahead of one’s own personal beliefs” (9.25 – Table 1 and 9.6 – Table 2). Perhaps generic values are “easy” to endorse until certain “pushes” come to “shoves.”

Another is the consistent middle-of-the-pack ranking for responding to societal needs – particularly given the high profile within the professions and social contract literatures on medicine’s obligations to respond to public needs. Next time, we will provide examples of student rewrites to Swick’s call to social responsibility.

Swick’s placement of two accountability items in his original list of 10 also reflects a consistent sociological argument that self-regulation is core to what it means to be a profession and to related constructs such as medicine’s social contract with society.2 While students appear responsive to a general call to accountability, they balk at the specifics of holding colleagues accountable and of reporting those who fail to uphold professional standards. Again, and next time, we will see rewrite examples of how these two items, particularly the latter, come to be seen in a more copacetic light.

I have four more general comments tied to these data: First, Swick’s behaviors of professionalism are all framed as behaviors of… physicians. As such, Swick’s “call” both reflects and feeds a shift from earlier, and more sociological, foci on “the profession” to a reframing of professionalism (within medicine’s modern day professionalism movement) at the level of the individual.2

Second, Swick’s original ten items are a combination of inner-directed (e.g., honesty, integrity) and outer-directed (e.g., peers, patients, or the public) attributes. Possible differences in these and other internal differentiators are worth exploring – although I will not do so here.

Third, and expanding on an earlier item, I think it is worth reflecting on the differences between Swick’s original 10 and Ed Hundert’s additions three. Two of Hundert’s “3” focus on the tensions between work/home and self/others. The third (the placement of professional ethics over personal beliefs) is another type of tension and was not well received by students. I found mean scores tied to work/home and self/others tensions result to be somewhat surprising given these are students who were attending medical school (2004, 2009) quite earlier than the widespread rise of concerns within the medical and medical education literatures about burnout, well-being, and work-life balance. Perhaps, and perhaps like some of the other exercise items we already have explored, there is a canary-in-the-coal-mine nature to these data.

Fourth, I want to reiterate what I see as a key revelation in these two and Swick Exercises in general – that students have long nurtured considerable concerns and equivocations about professionalism and what it means to be a good doctor.

Finally, I want to return to altruism’s “fall from grace.” This remains the signature finding in these two Swick exercises. Whatever the liturgical source, be it professionalism codes, charters, competencies or curricula, students continue to face a cacophony of calls to “selfless duty” and to place “patient welfare ahead of one’s own” – now within an emerging presence of yet additional “interests” (corporate and otherwise). Traditions and ritualistic calls aside, and echoing Daniel Ofri’s concerns that corporate interests have come to subvert the profession’s commitment to altruism,3 the loss of physician control over its work, coupled with calls by employers for physicians to sacrificially meet patient needs in the face of corporate restrictions and rationalizations, signals a profession under assault.4

Next: Part 4: The Rewrites

REFERENCES

- Swick, Herbert M. 2000. Toward a Normative Definition of Medical Professionalism. Acad Med 75 612-16.

- Hafferty, FW. 2018. Academic Medicine and Medical Professionalism: A Legacy and a Portal into an Evolving Field of Educational Scholarship. Acad Med 93 (4): 532-36.

- Ofri, Danielle. 2019 (June 8). The Business of Health Care Depends on Exploiting Doctors and Nurses. New York Times, Section SR, Page 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/08/opinion/sunday/hospitals-doctors-nurses-burnout.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share

- Malina, Debra, Atheendar S Venkataramani, Lisa Rosenbaum, Genevra Pittman, and Stephen Morrissey. 2025. The Corporatization of U.S. Health Care - a New Perspective Series. N Engl J Med 393 (1): 81-82.

Frederic W. Hafferty, PhD is a medical sociologist and Senior Fellow, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Back to Table of Contents

|

APHC Roundtable

Friday, October 10 at 3 p.m. ET

|

Advancing Leadership, Insight, Growth, and Nurturing in Healthcare through Coaching with Dr. Susan Parisi and Dr. Halle Ellison

In healthcare, what we often label as “unprofessional behavior” may actually be the visible tip of a deeper, invisible struggle—burnout, moral injury, or emotional exhaustion. Instead of reacting with correction, what if we responded with curiosity and compassion?

What if we saw these moments not as failures, but as signals, as opportunities to offer proactive support before burnout? Coaching invites clinicians into a space of reflection, helping them build self-awareness, reconnect with their values, and grow personally and professionally. Through this lens, we begin to see individuals not as problems to fix, but as whole and capable people navigating complex systems. The ALIGN Coaching Program is built on this belief.

Join Dr. Halle Ellison and Dr. Susan Parisi for a dynamic session exploring the intersection of burnout, unprofessional behavior, the power of coaching to support individuals, and a model for aligning individual support with organizational change.

Register at: https://bit.ly/APHCRoundtables

Dr. Susan Parisi joined Geisinger as the Chief Wellness Officer in July of 2022. She brings three decades of experience in healthcare, spending the earlier part of her career caring for patients in obstetrics and gynecology. She’s held leadership roles in several organizations, most recently serving as the director of well-being for Nuvance Healthcare, where she worked to implement a strategic and collaborative well-being program that accommodates seven hospitals, a multispecialty group and 2,500 physicians across New York and Connecticut.

After supporting fellow physicians through their own experiences with burnout and emotional exhaustion, Dr. Parisi pursued the prestigious Stanford Chief Wellness Officer training, which she completed in 2019. In 2018, she completed a fellowship in integrative medicine at the University of Arizona. She earned her Bachelor of Science with a concentration in genetics and development from Cornell University and her medical degree from New York Medical College. She serves on several boards and committees, and is an active member of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Dr. Halle Ellison is a board-certified general surgeon and hospice and palliative medicine physician. She serves as the Director of Physician and Advanced Practice Provider Well-being at Geisinger and is an Associate Professor of Medical Education at Geisinger College of Health Sciences. Dr. Ellison earned her MD from Ross University and holds a Master of Applied Science in Patient Safety and Healthcare Quality from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

She has held multiple roles in undergraduate and graduate medical education. Nationally, she contributes to initiatives through the AAMC, the American College of Surgeons, and the Academy for Professionalism in Health Care, where she serves on the board of directors. Her scholarly work spans palliative care, medical education, and clinician well-being. Dr. Ellison is committed to driving systems-level change to support health professional well-being and to educate the next generation of clinicians.

Roundtables are for APHC Members only.

Check out our membership benefits here.

Join APHC to access previous Roundtable recordings.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Healthcare Professionalism: Education, Research & Resources Podcast

|

Professional Formation and APHC collaborate on a podcast, Healthcare Professionalism: Education, Research & Resources.

Over 125 podcast episodes have been released with over 17,000 downloads.

Released every other Saturday morning, recent episodes include Rachel Pittmann discussing Telehealth Etiquette and Amal Khidir talking about Designing the Faculty Development Professionalism Program with Multi-cultural Perspectives.

You can access the podcast episodes on your favorite platform or at: https://bit.ly/PF-APHC-Podcast

Back to Table of Contents

|

APHC Member Announcements

|

For those interested in questions of health professionalism associate with conscience considerations, check out Bryan Pilkington's new book: The Medical Act: Conscientious Practice in a World of Dissention and Disagreement, which comes out later this month.

If you are an APHC member, we will publicize your events, job searches, research, grants, articles, podcasts, books, etc., in the newsletter.

Back to Table of Contents

|

As a member, you have access to special benefits that include:

- Belonging to a community of like-minded professionals

- Participating in the monthly Professionalism Education

Roundtables with authors, faculty, and researchers, plus accessing past recordings

- Accessing 15 Professional Formation modules for individuals for free

- Enrolling in the APHC Faculty Development Certificate program known as LEEP (Leadership Excellence in Educating for Professionalism), which was launched in 2020 and offers longitudinal mentoring for a select group of

individuals seeking to deepen their knowledge and skills in

professionalism education, assessment, and research

- Posting your research, articles, podcasts, webinars, conferences, and books in the newsletter distributed to about 15,000 people

- Receiving a 20% discount on educational videos created by the Medical Professionalism Project, which also allows you to obtain MOC and CME

- Registering for APHC conferences with discounts

- Participating in APHC committees, which include the conference program, membership, and education committees

Our annual membership fees are very inexpensive and are valid for one year from the payment date. Select from seven types of membership, including the institutional membership for four people. See the descriptions.

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Academy Newsletter Editors

|

Editor-in-Chief: Bryan Pilkington | Managing Editor: Yvonne Kriss

Please contact Yvonne if you'd like to contribute an article to this newsletter.

If you know someone who would benefit from reading Professional Formation Update, please pass this along. They can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here.

|

Academy for Professionalism in Health Care

PO Box 20031 | Scranton, PA 18502

|

Follow us on social media.

|

|