Volume 8, Issue 7 - July/August 2025

|

The Double Issue: Professionals, Ethics, and Trust

By: Bryan Pilkington, PhD

|

Having grown up in a time when print media was still consumed, I am and remain a fan of the “double issue.” Often in the summer when things were hectic, various folks were on vacation this week or that, it was nice a receive a bit extra in terms of reading or content. The magazine or paper was a bit heavier. Those putting out the issue might have papered over the fact that two of the usually sized issues would be lengthier in total than the double issue, but c’est la vie. At The Academy, we are giving the double issue a try. If it suits you and your summer schedules, do let us know. Similarly, if its not for you, we would love to hear that, too. Having grown up in a time when print media was still consumed, I am and remain a fan of the “double issue.” Often in the summer when things were hectic, various folks were on vacation this week or that, it was nice a receive a bit extra in terms of reading or content. The magazine or paper was a bit heavier. Those putting out the issue might have papered over the fact that two of the usually sized issues would be lengthier in total than the double issue, but c’est la vie. At The Academy, we are giving the double issue a try. If it suits you and your summer schedules, do let us know. Similarly, if its not for you, we would love to hear that, too.

Our double issue focuses on professionals; in particular, what professionals think about ethics, trust, and – ultimately – professionalism. To achieve this end, we come at the topic from three vantage points. First, this double issue houses the second part of our miniseries by Fred Hafferty on the Swick Test. As with any good miniseries, parts must have subparts, plots have subplots and so you can enjoy the second part this month with a third (sub-a) and another third (sub-b) parts coming in the future. These terrifically interesting and insightful sections of Hafferty’s work are sure to engage the reader. If you missed the Preface or Part 1, do check out our past issues. Second, we have a work from Jocelyn Mitchell-Williams, Lawrence Weisberg, Amy Colcher, and Vijay Rajput on the relationship between trust and professionalism. Third, we reflect on the recent APHC conference, “Building and Rebuilding Trust: Reflection and Action in Professionalism,” where that very exercise in the aforementioned Part 2 took place! Elizabeth Kachur, Amal Khidir, Mary Horton, Sylvia Botros, and Kate Noonan describe key features of the conference in a thoughtful and timely retrospective piece. Finally, the issue concludes with a review of Tom Koch’s recently published book: Seeking Medicine’s Moral Centre: Ethics, Bioethics, and Assisted Dying.

The issue includes the usual announcements and member accomplishments, as well as professionalism-related events of note, and information about the upcoming roundtable.

Bryan Pilkington, PhD is Editor-in-Chief of The Academy: A Forum for Conversations about Health Care Professionalism

|

The Swick Exercise: Part 2

By: Frederic W. Hafferty, PhD

|

The Exercise: Background

Swick’s article,1 with its core list of 10 professionalism behaviors, was pivotal in my professionalism work for two reasons. First, Swick’s approach was profoundly sociological in its capturing of professionalism both at the level of individuals and also the profession. Second, Swick’s article, already a part of my 4-module professionalism curriculum, was about to become even more essential in my work on professionalism going forward.

In 2004, and guided by the about-to-be sundowned four-part module, which included exercises asking students to rank core (professionalism) competencies, identify those competencies they felt were strengths and weaknesses, rewrite competencies they “had difficulty endorsing,,” and the underlying reasons for why they would see classmates as someone they would (and would not) select as their own physician,2 I decided to take the “Swick’s 10” and make this the basis of a stand-alone, in-class, exercise. I wanted to know whether the range of pushbacks I had been witnessing within my professionalism modules was an aberration or temporary professionalism blip. More important, I wanted to continue to explore what things looked like “from the other side,” buttressed by an inherent belief that students would (continue to) teach me more about the professionalism landscape than I might teach them.

The Exercise: Construction

The exercise itself evolved across three decision points and in collaboration with two colleagues. First, was the decision to use Swick’s 10 normative behaviors unchanged - at least with respect to their ordering and wording. The only substantive alteration was to take Swick’s overall normative frame and begin each behavior statement with the precursor “Physicians must….” I wanted to make Swick’s normative approach even more explicitly social and normative. As such, I rejected other auxiliary verbs or phrases such as “should,” “could,” or “ought to” as being not normative enough. Swick’s first behavior (“Physicians subordinate their own interests to the interest of others”) thus became “Physician’s must subordinate their own interests to the interest of other.” Each of other 9 behaviors received the same prefix.

The second decision came in discussions with colleague Ed Hundert (then a dean at Harvard medical school). Ed and I previously had collaborated on hidden curriculum work, and during one routine conversation, we reviewed the Swick items. Ed wanted to add “a couple more” - in the end, three. These were simply appended to the original list of 10 thus generating a “new” list of 13 behaviors.

The third decision, was perhaps the most pivotal and came during ongoing discussions about professionalism with fellow sociologist, and professionalism co-author Brian Castellani.3 Somewhere during the course of our overall discussions, which included the data generated in the previous four-module set of exercises – which included students being asked to rewrite items they had trouble endorsing - Brian thankfully insisted that students be given the opportunity to take one of the “Swick-13” that they had trouble endorsing (their choice), and rewrite that behavior so that they could endorse it.

That was it. The “Swick Exercise” became the Swick’s original 10, Hundert’s additional three, and Castellani’s insistence on a one-item rewrite. There were no ponderings about scale construction, item validity, question rewording, or related constructs. This was a class exercise - nothing more, but also nothing less.

The next decision point was “the how” with a quick decision to ask students to do a forced ranking (1-13) as to “how important” they saw each item in terms of “being a good physician.” (see a copy of the actual exercise below). Students were explicitly told that a ranking of 11, 12 or 13 did not mean the behavior was unimportant or otherwise counter to being a good physician, just that they saw other items as more important.

The last overall decision was to replicate a feature of the earlier four-part module and return all data to students by the next class. This meant generating mean rankings for all thirteen items along with students receiving all of the rewritten items grouped by item #. The intent was to take what the class had produced and open it up to discussions about possible differences between the official professionalism curriculum and what they (personally and as a class) thought about things.

The exercise became (in large part because of what students had to say both on the exercise and in the discussion sessions) a foundational part of my own thinking and writing on professionalism. Over the ensuing years, I had occasional opportunities to “do Swick” with other groups, including nursing staff, pipeline minority students, medical students at other medical schools, and most recently, board members at a medical specialty retreat. Occasionally, other faculty expressed an interest in the exercise – including one who wanted to compare students across 6 health science schools – but alas this most interesting excursion never happened.

Next: Results.

REFERENCES

- Swick, Herbert M. 2000. Toward a Normative Definition of Medical Professionalism. Acad Med 75 612-16.

- Hafferty FW. What medical students know about professionalism. Mt Sinai J Med. 2002 Nov;69(6):385-97. PMID: 12429957.

- Hafferty, Frederic W., and Brian Castellani. 2010. The Increasing Complexities of Professionalism. Acad Med 85 (2): 288-301.

Frederic W. Hafferty, PhD is a medical sociologist and Senior Fellow, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Deconstructing Professionalism Through the ABI Model of Trust

By: Jocelyn Mitchell-Williams, Lawrence Weisberg, Amy Colcher, Vijay Rajput

|

In modern healthcare, professionalism and trust are inextricably linked. The erosion of trust—both at the bedside and in society—reflects a broader crisis in professionalism (Mitchell-Williams et al., 2025). As educators and institutions seek to restore and reinforce professional identity in health professionals through structured, evidence-informed approaches, the ABI model—comprised of Ability, Benevolence, and Integrity—offers a robust framework for understanding and cultivating trustworthiness in learners and practitioners. We have used the ABI model to deconstruct the process of trust assessment and provide a mechanism to mitigate judgment bias, thereby supporting the cultivation of professionalism in medical education and practice.

Trust and trustworthiness are essential in healthcare. They form the foundation of patient-physician relationships, interprofessional collaboration, and the societal privileges conferred upon the profession. Trust is an attitude—a belief formed through trust assessment, the process by which one evaluates another’s trustworthiness. However, trust is inherently uncertain. It arises in situations where outcomes are unpredictable and evaluators must rely on limited, often ambiguous information. In such contexts, human judgment is prone to bias. Judgment under uncertainty is frequently guided by heuristics—cognitive shortcuts that simplify complex evaluations but may introduce error. Well-documented biases such as anchoring and confirmation bias, including the “halo effect,” are common in clinical and educational settings. For example, an evaluator may perceive a learner who communicates well as generally competent (confirmation bias/halo effect) or may resist updating a prior negative judgment despite evidence of improvement (anchoring bias). Additionally, social and cultural stereotypes may unconsciously influence assessments, leading to disparities in the evaluation of trainees from marginalized backgrounds.

The ABI model, developed by Mayer et al., offers a systematic approach to trust assessment that helps minimize these biases. It proposes that trustworthiness comprises three dimensions: Ability (technical and interpersonal competence), Benevolence (genuine concern for others), and Integrity (adherence to moral and ethical principles). Like other cognitive forcing strategies, the ABI mnemonic shifts evaluators from heuristic-driven, intuitive System 1 thinking to deliberative, analytical System 2 thinking, thereby reducing bias. When evaluators assess learners using these separate components, they are encouraged to focus on specific, observable behaviors rather than global impressions. This structure enhances the transparency, fairness, and accuracy of the assessment process.

For example, the “Trust and Professionalism” workshop presented at the 2025 APHC Conference used case-based discussions to illustrate how the ABI framework can inform evaluations. One case involved Jonathan, a third-year medical student who turned off his pager during a night shift, missing a critical evaluation. Rather than labeling this behavior broadly as unprofessional and Jonathan as untrustworthy, the ABI model prompts evaluators to consider: Does this reflect a lack of ability to manage stress? Is his benevolence toward the team intact despite poor judgment? Was there a lapse in integrity, or was the behavior rooted in insecurity? Breaking the behavior into dimensions allows faculty to provide targeted feedback and tailor remediation to the learner’s developmental needs.

In another case, Jordan, a first-year student, submitted a differential diagnosis copied from a blog. The evaluator might initially label this behavior as “unprofessional” and view Jordan as untrustworthy. The ABI model, however, encourages a more nuanced assessment: Does Jordan demonstrate the ability to perform the task? Is there a genuine commitment to the learning community (benevolence)? Did the act reflect a failure of integrity, or was it due to a misunderstanding of academic norms? These questions prompt dialogue about group dynamics and the clarity of academic expectations. Such assessments promote fairness and support constructive growth.

By applying the ABI model in feedback and evaluation, educators can create shared language and criteria, reduce misunderstandings, and foster reflective dialogue. Beyond individual evaluations, the ABI framework supports a culture of professionalism in learning environments. When faculty explicitly model and teach the components of trustworthiness, students are more likely to internalize these values as central to their professional identity. Embedding discussions of ability, benevolence, and integrity into curricula helps develop self-aware, ethically grounded practitioners prepared to meet the complex demands of modern medicine.

Conclusion

The ABI model offers a powerful framework for reconstructing professionalism through the lens of trust. By deconstructing trust into its core dimensions and clarifying assessment criteria, the ABI approach reduces bias and promotes fairness in medical education.

Author Affiliations

- Jocelyn Mitchell-Williams, MD, Senior Associate Dean for Medical Education, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University

- Lawrence Weisberg, MD, Associate Dean for Professional Development; Director, Edward D. Viner Center for Humanism, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University

- Amy Colcher, MD, Director of Professionalism, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University

- Vijay Rajput, MD, Chair, Department of Medical Education, Nova Southeastern University, Dr. Kiran C. Patel College of Allopathic Medicine

Further Reading

- Mitchell-Williams, J., Weisberg, L. S., Colcher, A., & Rajput, V. (2025). Deconstructing professionalism through the ABI model of trust and trustworthiness for health professional learners and practitioners [Conference workshop materials]. APHC National Conference.

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Trust Building and Research Recommendations: Reflections from Post-Conference Round Table Conversations

By: Elizabeth Kachur, Amal Khidir, Mary Horton, Sylvia Botros, Kate Noonan

|

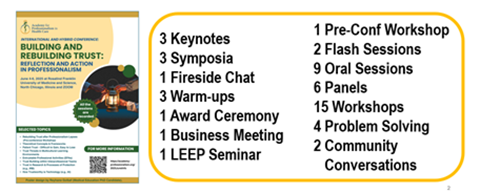

The monthly APHC Roundtable Discussion on July 11, 2025, focused on the recent hybrid APHC conference on Building and Rebuilding Trust: Reflection and Action on Professionalism. The event included 209 registrants from 16 different countries. Figure 1 lists the various individual sessions that were offered.

Fig 1. 2025 Hybrid conference sessions focusing on Building and Rebuilding Trust

A few weeks after the conference, the monthly APHC Roundtable Discussion took the theme to the next level by developing recommendations for trust building and by identifying some key questions to stimulate further research in this area. Two conference keynote presenters (Olle ten Cate and Michael Stawnychy) and a panelist from the Trust Building in Different Contexts Symposium (Saul Weiner) were present as well. Half of the Roundtable participants had attended the conference itself. Some of the hybrid event highlights are described in the June 2025 APHC Newsletter by Pilkington.

Following a brief conference recap, the Roundtable broke into small groups to brainstorm recommendations for building and rebuilding trust in the context of Education, Patient Care and Public Health. They also identified areas where further research is warranted to explore the issues of trust that are so critical to professionalism. We are grateful to Lyn Sonnenberg, Tanya Adonizio and Ann Blair Kennedy for serving as small group reporters. Below are the discussion results:

General Recommendations for Building, Sustaining and Rebuilding Trust

- Start with one-on-one and small group interactions then move to systems

- Listen to and empower the other person(s)

- Co-create meaning and understanding

- Maintain transparency around communications and expectations

- Consider the important role of linguistics (e.g., conflation of language)

- Reach out and partner with community members and organizations since systems are embedded in them

- Assure that organizations speak out loudly and explicitly about distrust and distancing

|

Questions that Need Further Explorations

|

Patient Trust in Learners & Practitioners

- How can learners demonstrate that they are trustworthy?

- Can we make clinicians trustworthy if the system has created much distrust?

|

Learner Trust in Faculty

- How can learners balance making a good impression and presenting with humility to faculty?

- Can learners trust preceptors when a power differential exists?

|

|

Patient Trust in Systems

- How can we embed relational ethics into professionalism in environments that are driven by transactional structures?

- How do you fit professionalism and trust into a system that is built on a culture of risk management and moral hazard, and that does not trust patients?

|

Provider Trust in Systems

- Can a clinician build trust with individual patients when the system creates much distrust?

- Where is the place for professionalism when dealing with insurance companies that inherently distrust not only patients, but also practitioners?

- What are the epistemological commonalities of all systems?

|

Table 1. Some key questions to explore best practices for establishing trust in learners, practitioners, patients, faculty and systems

In summary, trust building is complicated and needs to be addressed on many different levels. Open communications and partnering with individuals and communities are critical elements for building a context where trust is valued and can develop. There are still many unanswered questions about best practices for establishing trust in educational, clinical, institutional and community settings. The barriers to overcome are manifold, deeply rooted in past experiences and misinformation that are often not easy to uncover or change. Much more work needs to be done to enhance our understanding of how to improve trust building which is so fundamental to effective relationships and work on all levels.

Additional reflections on the Trust theme can be found in the current Newsletter issue. We encourage everyone to continue discussions on this topic which is so central to professionalism. Recordings of the July 11, 2025 Roundtable Discussion can be found here. Further resources on the topic are listed below.

|

Please consider joining us for upcoming events:

- APHC Education Roundtables are held on the second Friday of each month at 3:00 p.m. EST.

- APHC Conferences take place in June (hybrid format) and November (virtual format).

- Next Virtual APHC Conference related to Professionalism and Change: November 12 & 13, 2025, 8am-1pm EST. Call for Proposals will follow shortly.

|

Resources Shared During the Conference and the Roundtable Discussion

Publications

Web-based Resources

- International Clinician Educators (ICE) Blog: The Paradox of Trust – Where there is smoke, there may be a Fire https://icenet.blog/2025/07/10/the-paradox-of-trust-where-there-is-smoke-there-may-be-a-fire/#respond (contributed by Olle ten Cate)

- Patient Engagement Studio – a University of South Carolina program that connects patients and researchers to facilitate collaboration https://sc.edu/about/centers_institutes/patient_engagement_studio/index.php (contributed by Ann Blair Kennedy)

- Contextualized Care (adjusting care to patients’ context and needs) – a website that links to books and podcasts https://www.contextualizingcare.org/ (shared by Saul Weiner)

- The Science of Trust Initiative – a Journal of Communication in Healthcare (JCHC) article collection to develop a body of knowledge related to building and restoring trust in healthcare and public health https://www.tandfonline.com/journals/ycih20 search for Science of Trust Initiative (shared by Renata Schiavo during the conference)

- Medhum.org – a collection of reviews, essays and opinion pieces aimed to explore the human condition as expressed through medicine, literature and the arts https://medhum.org/ (shared by Lucy Bruell during the conference)

- Coalition for Trust in Health and Science – a collaborative of organizations committed to enhance trust building in healthcare education and practice https://trustinhealthandscience.org/ (shared by Michael Stawnychy and Mary Naylor during the conference)

Back to Table of Contents

|

Centering Ethics in Medical Practice: Conflicts in Professionalism

By: Bryan Pilkington, PhD

|

In his recent book, Seeking Medicine’s Moral Centre: Ethics, Bioethics, and Assisted Dying (Ethics International Press, 2024), Dr. Tom Koch pulls together a variety of interesting and thought-provoking arguments related to bioethics and the practice of medicine, with special attention to the relationship of caring between health professionals and patients. This latter thematic focus is most clearly seen in the arguments about an analysis of assisted dying, particularly in Canada, but it is an important theme throughout the text. This book does not – if it is proper to analogize a work in critical ethics to a boxer – pull any punches. It is, without a doubt, worth reading for those interested in bioethics, medical ethics, and the power or narrative and careful reflection on the changes in value-laden social practices (of which assisted dying is Koch’s main target).

Twenty-six chapters comprise Seeking Medicine’s Moral Centre and those chapters are divided into four helpful sections. The first section addresses issues associated with medical termination, and takes up considerations of dignity, euthanasia, physician assisted suicide, and medical aid in dying, among others. The second section engages considerations of difference, and addresses philosophical conceptions of normalcy, as well as disability. The third section, medical ethics, addresses a host of topics in that rich and interesting academic space, including care and compassion, the Hippocratic roots of medicine, and a critical appraisal of the field of bioethics. The fourth, and final, section offers a discussion.

The book touches on a great number of topics and so (as with many a book review) this short article will not serve the reader were it to attempt to comment on each of the argumentative threads nor will space allow a detailed summary of those arguments. However, one of Koch’s explorations is especially germane to the subject matter of The Academy, and so I focus the remainder of this review there with apologies for leaving out so many conversation-starting arguments and claims.

For those interested in healthcare professionalism, I would encourage you to read the text and reflect on the relationship between the practice of a profession and the moral center of that embodied practice. The twenty first chapter repays rereading on this very subject. Titled “The Ethical Professional as Endangered Person: Blog Notes on Doctor-Patient” and co-authored with Sarah Jones, this is a powerful chapter that critically engages professionalism. After situating their argument amid – what they see – as a host of work in professionalism, they depart from such threads rooted in professional or social values or the changes thereto and impacts on patients, instead exploring the “what appear to be the deleterious effects of professionalism, as taught today, as an ethical stance on physicians themselves” (176). The premise of the argument is urgent and will raise, for scholars of professionalism, as well as teachers of health professionals and practicing professionals themselves, significant questions. Ethics and professionalism are often thought to go hand in hand or, at least to be complementary. For Koch (and Jones), this is not the case. Rather, the problem, as they articulate it, is:

Medical students in the UK and North America are educated to a conflicting set of instructions. They are enjoined to take clinical responsibility for patients under their care while remaining emotionally and personally distant…they are expected to demonstrate a series of interpersonal and social values that include compassion (ACGRE 1999) and generosity (Frank 2004) in the treatment of persons whose individual realities are to be seen at best empathetically but never sympathetically (Erde 2008).

Put another way, medicine is now practiced by institutions, not by persons embedded within a community. These two claims – the restriction of emotional attachment to patients and the practice of medicine by institutions may appear to be distinct claims; however, much like the three formulations of Kant’s categorical imperative, they ought to be – I believe – understood as a different version of the same claim.

The practice of medicine, indeed the practices of many health professions, is challenging. The work is demanding; it can be emotionally fraught, and it can – at times – be thankless. One of the features that marks out the work of medicine as the work of a profession is the altruistic nature of the endeavor coupled with specialized knowledge that can yield practical benefits. It my be that altruism does a good deal of the philosophical heavy lifting in justifying the demands on health professionals, but to Koch (and Jones)’s credit, they seek not to aid professionals in avoiding burnout by reinforcing a sterilizing, unfeeling relationship between patients and practitioners, but rather they encourage us all to recognize the humanity in the other. Through greater identification with patients, professionals might avoid the moral distress and burnout that that very distance is supposed to (at least in part) address.

Reflecting on this relationship between health professionals and patients gains a new dimension when following Koch (and Jones)’s that medicine is practiced within institutions and not embedded within communities. There are, to be sure community hospitals and communities of practice – two different kinds of communities – but, to their point, many patients now seek the care of a health system, not of a named, individual physician. Today’s patient is more likely to say, “I had my appendix removed at…,” not “I had my appendix removed by…” Relationships between persons is distinct from relationships between individuals and institutions. As the late philosopher and ethicist Alasdair MacIntyre argued in his well-known book After Virtue: institutions corrupt practices. This is not to say that health systems cannot be wonderful and caring places, but that the kind of care the Koch is interested in supporting throughout his book is the care by a physician, or another health professional, for a patient. When persons, including health professionals, are not embedded in communities in the ways in which they may once have been and do not have opportunities for the kinds of relationships (those that had gone under the moniker the doctor-patient relationship), it raises the question of whether medical care is being offered and how? It is the question with which I leave the reader and in forming your answer I suggest reading this new and provocative text: Seeking Medicine’s Moral Centre: Ethics, Bioethics, and Assisted Dying, by Tom Koch.

Bryan Pilkington, PhD is Professor in the Department of Medical Sciences at the Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine

Back to Table of Contents

|

APHC Roundtable

Friday, August 8 at 3 p.m. ET

|

Trusting Communications with Dr. James (Jay) Joseph, MD, MSPC, HMDC, FAAFP

This presentation will be an interactive discussion exploring the essential role of trust in healthcare and education. The discussion will focus on:

- Participants' experiences with serious illness care

- Ethical principles setting a foundation for all trusting relationships, including those in medicine and education

- Brene Brown's "Anatomy of Trust" using the BRAVING framework

Register at: https://bit.ly/APHCRoundtables

Dr. Joseph is a board-certified family physician and hospice medical director serving as Medical Director of Geisinger at Home Palliative Care Service through which he provides and oversees patient care in the home setting throughout rural Pennsylvania. As Geisinger Respecting Choices® Faculty, he is leading a system-wide strategy to transform care to a more person-centered approach. He is faculty for Geisinger’s Palliative Medicine fellowship and for Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine.

Prior to his current roles, Dr. Joseph practiced primary care family medicine for 20 years, first with the U.S. Army, then in rural Pennsylvania. He served on the Board of the Pennsylvania Academy of Family Physicians and is past President of The Bloomsburg Hospital medical staff.

Dr. Joseph earned his bachelor’s degree from The Pennsylvania State University, his medical degree from The Jefferson (now Sidney Kimmel) Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University, and his master’s degree in palliative care from the University of Maryland.

Roundtables are for APHC Members only.

Check out our membership benefits here.

Join APHC to access previous Roundtable recordings.

Back to Table of Contents

|

Healthcare Professionalism: Education, Research & Resources Podcast

|

Professional Formation and APHC collaborate on a podcast, Healthcare Professionalism: Education, Research & Resources.

Over 125 podcast episodes have been released with over 17,000 downloads.

Released every other Saturday morning, recent episodes include Rachel Pittmann discussing Telehealth Etiquette and Amal Khidir talking about Designing the Faculty Development Professionalism Program with Multi-cultural Perspectives.

You can access the podcast episodes on your favorite platform or at: https://bit.ly/PF-APHC-Podcast

Back to Table of Contents

|

APHC Member Announcements

|

- Dr. Sofica Bistriceanu, MD, PhD, was named one of the Top 20 Business Leaders Setting the Pace for 2025 by Entrepreneur Mirror.

- Bryan Pilkington, PhD published his book The Medical Act: Conscientious Practice in a World of Dissention and Disagreement.

If you are an APHC member, we will publicize your events, job searches, research, grants, articles, podcasts, books, etc., in the newsletter.

Back to Table of Contents

|

As a member, you have access to special benefits that include:

- Belonging to a community of like-minded professionals

- Participating in the monthly Professionalism Education

Roundtables with authors, faculty, and researchers, plus accessing past recordings

- Accessing 15 Professional Formation modules for individuals for free

- Enrolling in the APHC Faculty Development Certificate program known as LEEP (Leadership Excellence in Educating for Professionalism), which was launched in 2020 and offers longitudinal mentoring for a select group of

individuals seeking to deepen their knowledge and skills in

professionalism education, assessment, and research

- Posting your research, articles, podcasts, webinars, conferences, and books in the newsletter distributed to about 15,000 people

- Receiving a 20% discount on educational videos created by the Medical Professionalism Project, which also allows you to obtain MOC and CME

- Registering for APHC conferences with discounts

- Participating in APHC committees, which include the conference program, membership, and education committees

Our annual membership fees are very inexpensive and are valid for one year from the payment date. Select from seven types of membership, including the institutional membership for four people. See the descriptions.

Back to Table of Contents

|

The Academy Newsletter Editors

|

Editor-in-Chief: Bryan Pilkington | Managing Editor: Yvonne Kriss

Please contact Yvonne if you'd like to contribute an article to this newsletter.

If you know someone who would benefit from reading Professional Formation Update, please pass this along. They can subscribe to the newsletter by clicking here.

|

Academy for Professionalism in Health Care

PO Box 20031 | Scranton, PA 18502

|

Follow us on social media.

|

|